- Home

- Sylvia Plath

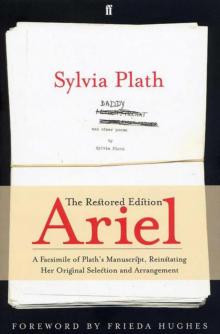

Ariel: The Restored Edition

Ariel: The Restored Edition Read online

Ariel

THE RESTORED EDITION

A facsimile of Plath’s manuscript,

reinstating her original selection

and arrangement

Sylvia Plath

Foreword by Frieda Hughes

Table of Contents

Title Page

Foreword

I: Ariel and other poems

Dedication

Morning Song

The Couriers

The Rabbit Catcher

Thalidomide

The Applicant

Barren Woman

Lady Lazarus

Tulips

A Secret

The Jailor

Cut

Elm

The Night Dances

The Detective

Ariel

Death & Co.

Magi

Lesbos

The Other

Stopped Dead

Poppies in October

The Courage of Shutting-Up

Nick and the Candlestick

Berck-Plage

Gulliver

Getting There

Medusa

Purdah

The Moon and the Yew Tree

A Birthday Present

Letter in November

Amnesiac

The Rival

Daddy

You're

Fever 103°

The Bee Meeting

The Arrival of the Bee Box

Stings

Wintering

II: Facsimile of the manuscript for Ariel and other poems

Ariel and other poems

III: Facsimile drafts of the poem ‘Ariel’

Ariel

APPENDIX I: ‘The Swarm’

The Swarm

APPENDIX II: Script for the BBC broadcast ‘New Poems by Sylvia Plath’

Notes

About the Author

Copyright

Foreword

This edition of Ariel by my mother, Sylvia Plath, exactly follows the arrangement of her last manuscript as she left it. As her daughter I can only approach it, and its divergence from the first United Kingdom publication of Ariel in 1965 and subsequent United States publication in 1966, both edited by my father, Ted Hughes, from the purely personal perspective of its history within my family.

When she committed suicide on February 11, 1963, my mother left a black spring binder on her desk, containing a manuscript of forty poems. She probably last worked on the manuscript’s arrangement in mid-November 1962. ‘Death & Co.’, written on the fourteenth of that month is the last poem to be included in her list of contents. She wrote an additional nineteen poems before her death, six of which she finished before our move to London from Devon on December 12, and a further thirteen in the last eight weeks of her life. These poems were left on her desk with the manuscript.

The first cleanly typed page of the manuscript gives the title of the collection as Ariel and other poems. On the two sheets that follow, alternative titles had been tried out, each title scored out in turn and a replacement handwritten above it. On one sheet the title was altered from The Rival to A Birthday Present to Daddy. On the other, the title changed from The Rival to The Rabbit Catcher to A Birthday Present to Daddy. These new title poems are in chronological order (July 1961, May 1962, September 1962, and October 1962) and give an idea of earlier possible dates of her rearrangement of the working manuscript.

When Ariel was first published, edited by my father, it was a somewhat different collection from the manuscript my mother left behind. My father had roughly followed the order of my mother’s contents list, taking twelve poems out of the U.S. publication, and thirteen out of the U.K. publication. He replaced these with ten selected for the U.K. edition, and twelve selected for the U.S. edition. These he chose from the nineteen very late poems written after mid-November 1962, and three earlier poems.

There was no lack of choice. Since the publication of The Colossus in 1960, my mother had written many poems that showed an advance on her earlier work. These were transitional poems between the very different styles of The Colossus and Ariel (a selection of them was published in Crossing the Water in 1971). But towards the end of 1961, poems in the Ariel voice began to appear here and there among the transitional poems. They had an urgency, freedom, and force that was quite new in her work. In October 1961, there was ‘The Moon and the Yew Tree’ and ‘Little Fugue’; ‘An Appearance’ followed in April 1962. From this point, all the poems she wrote were in the distinctive Ariel voice. They are poems of an otherworldly, menacing landscape:

This is the light of the mind, cold and planetary.

The trees of the mind are black. The light is blue.

The grasses unload their griefs on my feet as if I were God,

….

I simply cannot see where there is to get to.

(‘The Moon and the Yew Tree’)

Then, still in early April 1962, she wrote ‘Among the Narcissi’ and ‘Pheasant’, moments of perfect poetic poise, tranquil and melancholy—the calm before the storm:

You said you would kill it this morning.

Do not kill it. It startles me still,

The jut of the odd, dark head, pacing

Through the uncut grass on the elm’s hill.

(‘Pheasant’)

After that, the poems came with increasing frequency, ease, and ferocity, culminating in October 1962 when she wrote twenty-five major poems. Her very last poems were written six days before she died. In all, she left around seventy poems in the unique Ariel voice.

On work-connected visits to London in June 1962, my father began an affair with a woman who had incurred my mother’s jealousy a month earlier. My mother, somehow learning of the affair, was enraged. In July her mother, Aurelia, came to stay at Court Green, our thatched black and white cob house in Devon, for a long visit. Tensions increased between my parents, my mother proposing separation, though they travelled to Galway together that September to find a house where my mother could stay for the winter. By early October, with encouragement from Aurelia (whose efforts I witnessed as a small child), my mother ordered my father out of the house.

My father went up to London where he first stayed with friends, and then around Christmas rented a flat in Soho. He told me many years later that, despite her apparent determination, he thought my mother might reconsider. ‘We were working towards it when she died,’ he said.

Deciding against the house in Galway, my mother moved my brother and me to London in December 1962, to the flat she had rented in what was once Yeats’s house in Fitzroy Road. Until her death, my father visited us there almost daily, often babysitting when my mother needed time for herself.

Although my mother was in London for eight weeks before she died, my father had left her with their house in Devon, the joint bank account, the black Morris Traveller (their car), and was giving her money to support us. When my mother died, my father had insufficient funds to cover the funeral, and my grandfather, William Hughes, paid for it.

My father eventually returned to Devon with my brother and me in September 1963, when his sister, Olwyn, came over from Paris to help take care of us. She stayed with us for two years. My father continued to see ‘the other woman’ on visits to London, but she remained living primarily with her husband for two and a half years after my mother’s death.

Throughout their time together my mother had shown her poems to my father as she wrote them. But after May 1962, when their serious differences began, she kept the poems to herself. My father read ‘Event’ in the Observer that winter and was dismayed to see their private business made the subject of a poem.

My mother had descr

ibed her Ariel manuscript as beginning with the word ‘Love’ and ending with the word ‘Spring’, and it was clearly geared to cover the ground from just before the breakup of the marriage to the resolution of a new life, with all the agonies and furies in between. The breakdown of the marriage had defined all my mother’s other pain and given it direction. It brought a theme to the poetry. But the Ariel voice was there already in the poems of late 1961 and early 1962. It was as though it had been waiting, practising itself, and had found a subject on which it could really get a grip. The manuscript was digging up everything that must be shed in order to move on. ‘Berck-Plage’, for instance, written in June 1962, is about the funeral that month of a neighbour, Percy Key, but it is also tangled with the grievous loss of her father, Otto, when she was a child. My parents became beekeepers that summer, like Otto, who had been an expert on bees, and his presence stalks the five bee poems in the U.S. version of Ariel (four in the U.K. edition).

In December 1962, my mother was asked by BBC radio to read some of her poems for a broadcast, and for this she wrote her own introductions. Her commentaries were dry and brief and she makes no mention of herself as a character in the poems. She might expose herself, but she did not need to point it out. I particularly like two of them: ‘In this next poem, the speaker’s horse is proceeding at a slow, cold walk down a hill of macadam to the stable at the bottom. It is December. It is foggy. In the fog there are sheep.’ (‘Sheep in Fog’, though one of the poems she included in her broadcast with the Ariel poems, was not listed on my mother’s contents page in the manuscript—it was only finished in January 1963. My father included it in the first published version of Ariel.) For the title poem my mother simply writes: ‘Another horseback riding poem, this one called ‘Ariel’, after a horse I’m especially fond of.’

These introductions made me smile; they have to be the most understated commentaries imaginable for poems that are pared down to their sharpest points of imagery and delivered with tremendous skill. When I read them I imagine my mother, reluctant to undermine with explanation the concentrated energy she’d poured into her verse, in order to preserve its ability to shock and surprise.

In considering Ariel for publication my father had faced a dilemma. He was well aware of the extreme ferocity with which some of my mother’s poems dismembered those close to her—her husband, her mother, her father, and my father’s uncle Walter, even neighbours and acquaintances. He wished to give the book a broader perspective in order to make it more acceptable to readers, rather than alienate them. He felt that some of the nineteen late poems, written after the manuscript was completed, should be represented. ‘I simply wanted to make it the best book I could,’ he told me. He was aware that many of my mother’s new poems had been turned down by magazines because of their extreme nature, though editors still in possession of her poems published them quickly when she died.

My father left out some of the more lacerating poems. ‘Lesbos’, for instance, though published in the U.S. version of Ariel, was taken out of the British edition, as the couple so wickedly depicted in it lived in Cornwall and would have been much offended by its publication. ‘Stopped Dead’, referring to my father’s uncle Walter, was dropped. Some he might otherwise have taken out had been published in periodicals and were already well known. Other omissions—‘Magi’ and ‘Barren Woman’, for instance, both from the transitional poems—he simply considered weaker than their replacements. One of the five bee poems, ‘The Swarm’, was originally included in my mother’s contents list, but with brackets around it, and the poem itself was not included in her manuscript of forty poems. My father reinstated it in the U.S. edition.

The poems of the original manuscript my father left out were: ‘The Rabbit Catcher’, ‘Thalidomide’, ‘Barren Woman’, ‘A Secret’, ‘The Jailor’, ‘The Detective’, ‘Magi’, ‘The Other’, ‘Stopped Dead’, ‘The Courage of Shutting-Up’, ‘Purdah’, ‘Amnesiac’. (Though included in the 1966 U.S. version, ‘Lesbos’ was kept out of the 1965 U.K. edition.)

The poems he put into the edited manuscript for publication were: ‘The Swarm’ and ‘Mary’s Song’ (only in the U.S. edition), ‘Sheep in Fog’, ‘The Hanging Man’, ‘Little Fugue’, ‘Years’, ‘The Munich Mannequins’, ‘Totem’, ‘Paralytic’, ‘Balloons’, ‘Poppies in July’, ‘Kindness’, ‘Contusion’, ‘Edge’, and ‘Words’. ‘The Swarm’ was included in the original contents list, but not in the manuscript.

In 1981 my father published my mother’s Collected Poems and included in the Notes the contents list of her Ariel manuscript. This inclusion brought my father’s arrangement under public scrutiny, and he was much criticized for not publishing Ariel as my mother had left it, though the extracted poems were included in the Collected Poems for all to see.

My father had a profound respect for my mother’s work in spite of being one of the subjects of its fury. For him the work was the thing, and he saw the care of it as a means of tribute and a responsibility.

But the point of anguish at which my mother killed herself was taken over by strangers, possessed and reshaped by them. The collection of Ariel poems became symbolic to me of this possession of my mother and of the wider vilification of my father. It was as if the clay from her poetic energy was taken up and versions of my mother made out of it, invented to reflect only the inventors, as if they could possess my real, actual mother, now a woman who had ceased to resemble herself in those other minds. I saw poems such as ‘Lady Lazarus’ and ‘Daddy’ dissected over and over, the moment that my mother wrote them being applied to her whole life, to her whole person, as if they were the total sum of her experience.

Criticism of my father was even levelled at his ownership of my mother’s copyright, which fell to him on her death and which he used to directly benefit my brother and me. Through the legacy of her poetry my mother still cared for us, and it was strange to me that anyone would wish it otherwise.

After my mother’s suicide and the publication of Ariel, many cruel things were written about my father that bore no resemblance to the man who quietly and lovingly (if a little strictly and being sometimes fallible) brought me up—later with the help of my stepmother. All the time, he kept alive the memory of the mother who had left me, so I felt as if she were watching over me, a constant presence in my life.

It appeared to me that my father’s editing of Ariel was seen to ‘interfere’ with the sanctity of my mother’s suicide, as if, like some deity, everything associated with her must be enshrined and preserved as miraculous. For me, as her daughter, everything associated with her was miraculous, but that was because my father made it appear so, even playing me a record of my mother reading her poetry so I could hear her voice again. It was many years before I discovered my mother had a ferocious temper and a jealous streak, in contrast to my father’s more temperate and optimistic nature, and that she had on two occasions destroyed my father’s work, once by ripping it up and once by burning it. I’d been aghast that my perfect image of her, attached to my last memories, was so unbalanced. But my mother, inasmuch as she was an exceptional poet, was also a human being and I found comfort in restoring the balance; it made sense of her for me. The outbursts were the exception, not the rule. Life at home was generally quiet, and my parents’ relationship was hardworking and companionable. However, as her daughter, I needed to know the truth of my mother’s nature—as I did my father’s—since it was to help me understand my own.

But if I had ever been in doubt that my mother’s suicide, rather than her life, was really the reason for her elevation to the feminist icon she became, or whether Ariel’s notoriety came from being the manuscript on her desk when she died, rather than simply being an extraordinary manuscript, my doubts were dispelled when my mother was accorded a blue plaque in 2000, to be placed on her home in London. Blue plaques are issued by English Heritage to celebrate the contribution of a person’s work to the lives of others—and to celebrate their life in the place where they did the liv

ing. It was initially proposed that the plaque should be placed on the wall of the property in Fitzroy Road where my mother committed suicide, and I was asked if I would unveil it once it was in place. English Heritage had been led to believe that my mother had done all her best work at that address, when in fact she’d been there for only eight weeks, written thirteen poems, nursed two sick children, been ill herself, furnished and decorated the flat, and killed herself.

So instead, the plaque was put on the wall of 3 Chalcot Square, where my mother and father had their first London home, where they had lived for twenty-one months, where my mother wrote The Bell Jar, published The Colossus, and gave birth to me. This was a place where she had truly lived and where she’d been happy and productive—with my father. But there was outrage in the national press in England at this—I was even accosted in the street on the day of the unveiling by a man who insisted the plaque was in the wrong place. ‘The plaque should be on Fitzroy Road!’ he cried, and the newspapers echoed him. I asked one of the journalists why. ‘Because,’ they replied, ‘that was where your mother wrote all her best work.’ I explained she’d only been there eight weeks. ‘Well, then,’ they said, ‘… it’s where she was a single mother.’ I told them I was unaware that English Heritage gave out blue plaques for single motherhood. Finally they confessed. ‘It’s because that’s where she died.’

‘We already have a gravestone,’ I replied. ‘We don’t need another.’

I did not want my mother’s death to be commemorated as if it had won an award. I wanted her life to be celebrated, the fact that she had existed, lived to the fullness of her ability, been happy and sad, tormented and ecstatic, and given birth to my brother and me. I think my mother was extraordinary in her work, and valiant in her efforts to fight the depression that dogged her throughout her life. She used every emotional experience as if it were a scrap of material that could be pieced together to make a wonderful dress; she wasted nothing of what she felt, and when in control of those tumultuous feelings she was able to focus and direct her incredible poetic energy to great effect. And here was Ariel, her extraordinary achievement, poised as she was between her volatile emotional state and the edge of the precipice. The art was not to fall.

The Bell Jar

The Bell Jar Crossing the Water

Crossing the Water Ariel

Ariel The Colossus

The Colossus Mary Ventura and the Ninth Kingdom

Mary Ventura and the Ninth Kingdom The Letters of Sylvia Plath Vol 2

The Letters of Sylvia Plath Vol 2 The It Doesn't Matter Suit and Other Stories

The It Doesn't Matter Suit and Other Stories The Letters of Sylvia Plath Volume 1

The Letters of Sylvia Plath Volume 1 Ariel: The Restored Edition

Ariel: The Restored Edition Selected Poems of Sylvia Plath

Selected Poems of Sylvia Plath